Lenkiewicz produced a series of Projects in the 1970s which dealt with the nature of human relationships, such as Love & Romance (1975), Love & Mediocrity (1976), and human physiology in a state of crisis, such as Jealousy (1977), and Orgasm (1978). Each employed a distinctive visual style.

It’s true that I am very unattracted to the idea of exclusive relationships. We know that we are endlessly attracted to people; there is no end to it. We would not remember the first 300 lovers if we lived for 1,000 years – thank god we only live to seventy! – and their names would just mist away in time. And I challenge anybody who is the victim of the 50th golden wedding anniversary to tell me that they would like to be the victim of the 500th wedding anniversary with the same person! (The Leaves Were Full of Children, TSW 1982)

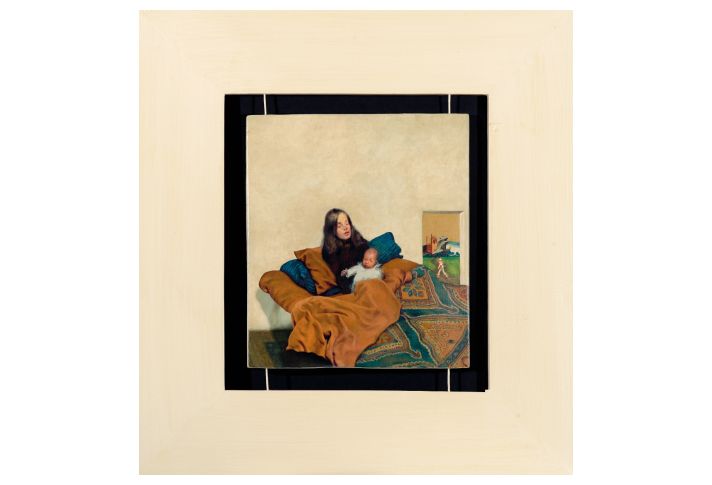

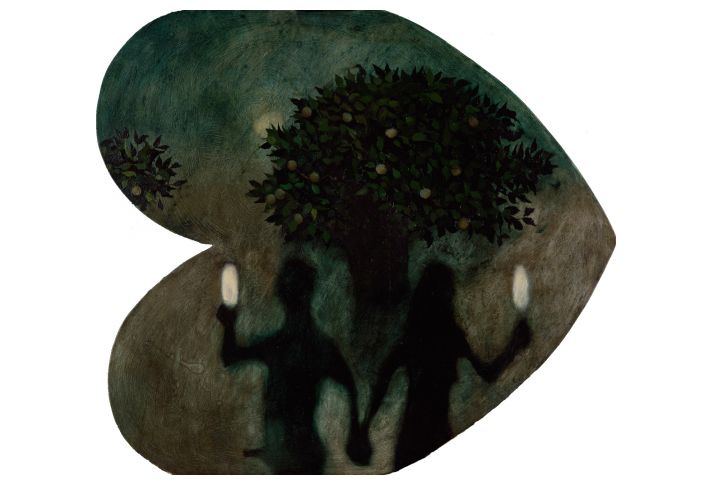

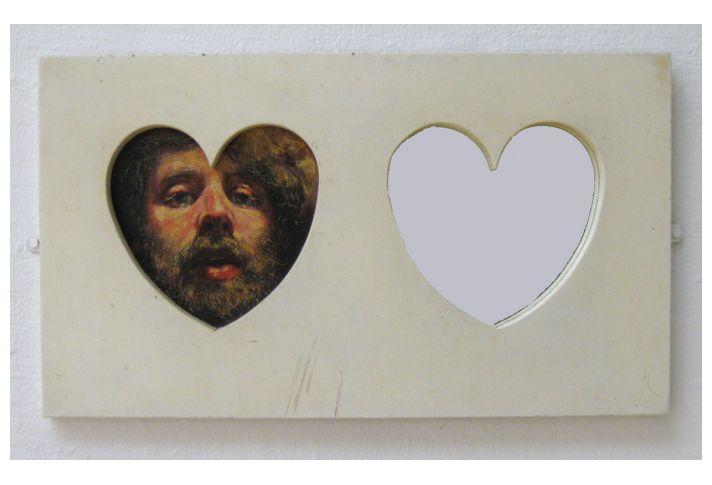

The idea of lovers as martyrs sacrificing themselves in the relationship would be worked out in Section Four of the Relationship Series, Love & Romance. Some of the oil paintings echo Christian iconography produced by Cranach, Mantegna or Pesellino, such as Lelya on the Cross with Pesellino’s Saints. Lenkiewicz wrote in the pamphlet given to exhibition visitors:

We are told of two thieves who hang by the side of a crucified man, (in romantic love, there are two thieves constantly stealing from each other, who finally crucify each other). We are further told of The Deposition, when the dead man is brought down from the cross and mourned (in romantic love, one partner grieves after the lost affections of the other). We are finally told that the dead man resurrected (in romantic love, the ‘loser’ in the attachment replaces the addiction with a new companion.)

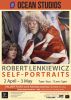

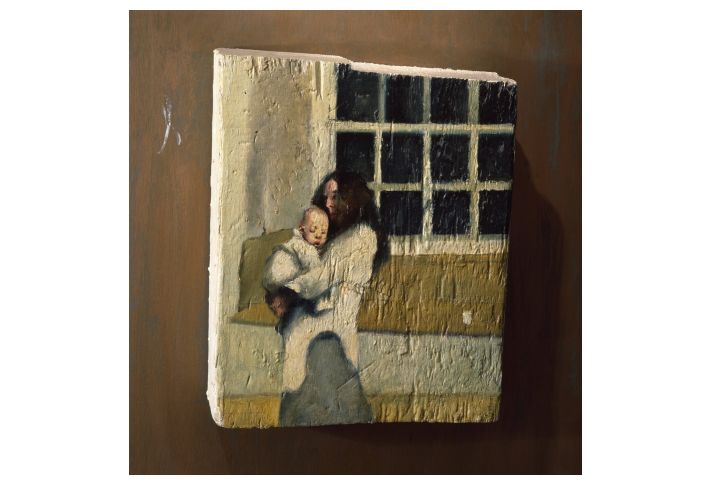

A recurring Project theme was "object with human still-life", such as Cup with Human Still-LIfe, which shows Annie with their newborn child. This displacement of the human figure into just another object of attraction illustrated the artist's thesis that all our attractions must be operating in the same physiological realm:

The aesthetic reaction to, shall we say, the woman, is not necessarily as dissimilar as our aesthetic reaction towards wallpaper, and clothing ... and ideologies.

Lenkiewicz’s extensive notes for Love & Romance (PDF avaialble) present the fossilized romantic metaphors surrounding the notion of love, from the abstemious troubadours of medieval courtly love, to the “love beyond” of Wuthering Heights and much besides. Lenkiewicz concluded that, even after the Free Love revolution of the Sixties, the “romantic philosophy” of his time still held that:

1) Sex is only good, beautiful and proper when it is accompanied by deep feelings of “love”.

2) Sex without “love” is relatively mild, a purely animal pleasure. With “love” it is soul-stirring and ecstatic bliss.

3) The same kind of sex relations that, without “love”, would be shameful may be indulged in regardless when they are experienced as part of a heavily romantic attachment.

4) Sex transformed by “love” becomes so rewarding that one does not give serious thought to copulating with another person.

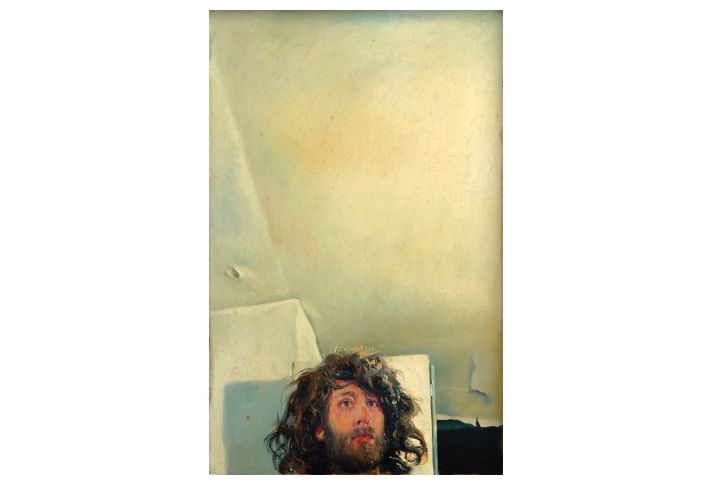

As anyone who has heard the gossip about the painter’s private life will know (or think they know), Lenkiewicz did not subscribe to any of these notions. The notes for his 1997 Retrospective at Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery give the clue: “an unrequited passion is the lifeblood of creativity”. Mouse, his former wife, puts it in these terms: “Robert only really fell in love with what he couldn’t have. As soon as he got that full measure of devotion he wasn’t interested”. And Lenkiewicz, naturally, had an ironic maxim for it:

“new mediocrities can haunt the mind more deeply than old profundities”.

Lenkiewicz prefaced his notes on Love & Romance with one of Nietzsche’s pithiest maxims:

It’s interesting how cunning Nietzsche could be, despite the fact that he had hardly any relationships with women. It’s a curious, ruthless and ironic humanism that characterizes some of Nietzsche’s perceptions. People are always quoting “Goest thou to women? Do not forget thy whip”, and stuff like that, and obviously there are difficulties and problems … but there is a certain type of cunning about a remark like “How nicely does doggish lust beg for a piece of spirit when a piece of flesh is denied it”. Very cunning, that remark. In a curious kind of way it’s a very experienced one, but his father was a pastor, he had a strong theological background, and only someone with a background of that kind could make that kind of remark. And it’s a brave one: “How nicely does doggish lust beg for a piece of spirit when a piece of flesh is denied it”. (1997)

In the Love & Romance booklet Lenkiewicz observes:

The curious nature of human affection seems structured in such a way that when it has “committed” itself to one other person it simply refuses to see the rest. If we find reasonably attractive one in every hundred persons we meet, let us even say one in every thousand, then we are aware that in relation to the present population we are finding, strongly attractive and to our personal taste, approximately 13 million men and women. By meeting just one of this army of possibilities we can, in many cases, find ourselves satisfied. This may be plain lifelessness or stupidity, but it does seem that many couples find genuine reward in exclusive relationships. A healthy suspicion may be levelled at such behaviour, for its very exclusiveness can so easily exclude the whole of the world.